Blog of Buddhism Teacher

Buddhism's Traditions and Schools

The practice of Buddhism throughout the world seems to adapt to the culture of the country of import. A variety of cultures merge beliefs with different dharma focuses, such as ethics and morals, science, meditation and psychology. The practice of Buddhism can vary, just as Christianity does for Catholics, Lutherans, Methodist, Baptists, Christian Scientists. There are two basic Buddhist traditions: Theravada and Mahayana.

As Buddhism spread south from the north of India the original tradition, Theravada, encompassed most of India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Burma (Myanmar), Cambodia and Laos. Today, only three countries are considered “Buddhist countries.” They are Sri Lanka, Thailand and Burma (Myanmar).

As Buddhism spread north to include Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, Vietnam, China, Korea and Japan, there were changes in some of the practices and the more liberal Mahayana tradition is the result. However, Mahayana divided into several schools, which today includes Vajrayana, Pure Land and Zen, although there are others.

Some consider Vajrayana a tradition, rather than a school, mainly because in Tibet, Buddhism merged with that culture’s ancient and indigenous religion of Bon. Tantra became influential in Nepal, Tibet, China, Japan, Java and Sumatra (Indonesia). Ch’an or Zen, the meditation school, became popular in China and Japan, Soka Gakkai began in Japan but has spread into the west, and Pure Land has roots in Tibet and China and is growing in the west. Both Zen and Vajrayana are growing in popularity in the west.

Both of these traditions and all of the schools can be found in the United States. Sometimes the different practices of Buddhism are incorrectly labeled ethnically or culturally, such as Korean Buddhism, Japanese Buddhism, Thai Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, etc. This is because as Buddhism spread to these different countries and cultures it absorbed some of each country’s traditions, ceremonial customs, and indigenous religious philosophies and beliefs.

It is important to understand, however, that the basic Buddhist teachings of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, which include, but are not limited to the teachings of karma and samsara, are basically the same in all traditions and schools. Methods of practice, explanations of dharma and some interpretations may differ, but the importance of practicing metta and karuna (loving kindness and compassion with action) is stressed by the sangha and all dharma teachers in each tradition and in all schools.

Emptiness

Sunyata (Sanskrit) and Sunnata (Pali) translates as “emptiness” in English. It is a basic concept in Buddhism and is stressed especially in some schools of Mahayana Buddhism, including Zen.

Emptiness teaches the lack of substantiality or independence of things, and stresses the idea of no independent origination, that the present state of all things is the result of a previous state. Emptiness includes the teaching of impermanence; everything is always in a state of change. In other words, everything, including every sentient being, is an ever-changing process.

The dharma of non-attachment relates to the concept of emptiness and impermanence, since if all things are impermanent and are always changing, what is there to be attached to? Being free of attachments is the true state of emptiness.

The Buddha taught that this is like this, because that is like that . . . and that is like that, because this is like this; this is called dependent co-arising.”

“It is not the river that flows, the flow is the river; and there is no riverbed – the flow is therefore empty.”

“You can’t step into the same river twice. Why? Because you and the river are constantly changing. The river does not stay the same and neither do you.”

“Where is the baby in your baby picture?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama refers to sunyata as “the knowledge of the ultimate reality of all objects, material and phenomenal.” Sunyata explains that everything is interrelated, interdependent and is without substance or soul.

Sunyata or emptiness does not mean that there is no existence of matter. It does not mean that there is no existence of feelings, perceptions or ideas. The five aggregates that comprise a sentient being, i.e., body, feelings, perceptions, mind formations or thought process, and consciousness, are impermanent, ever-changing and therefore empty. Forms or material things are compounded, the result of something else, the effect of a cause, and are therefore impermanent and empty.

Each of us is made of stardust, and even the stars are the result of something else. Can you imagine there being a beginning of anything and there being an ending? Name something that was not the result of something else and the cause of something else. How far back can we go in naming our ancestors? The human brain has a difficult time coping with the idea that there either is a beginning and an end, or that there is not.

The reason for the Buddhist teaching of emptiness is to loosen all attachments to views, stories and assumptions, leaving the mind empty of all greed, anger, and delusion; therefore, empty of suffering of stress, anxiety, frustration and unsatisfactoriness.

Karma

Karma (kamma) is one of Buddhism’s most misunderstood concepts and teachings. First off, karma is neither good nor bad; it is not the just result of action, and it isn’t one’s fate. Such misconceptions are obstacles in understanding the Dharma (Dhamma) or Buddha’s teaching concerning the continuing of the individual creation process through intention, volition (choice) and action.

Science’s law of cause and effect is a close parallel to the Buddhist “law” of karma, but it isn’t exactly the same. The biblical, “whatsoever a man shall soweth so shall he also reap,” isn’t either, although it’s in the same ballpark. Perhaps the closest is Webster’s definition, “the sum and the consequences of a person’s actions during the successive phases of his existence, regarded as determining his destiny.”

To fully understand karma, it is necessary to first understand Buddhism’s response to the age-old question, “Who am I.” Five khandhas or aggregates constitute a “human” or a “being”, according to the teaching. The first one is our body or form, with its four elements of solidity, fluidity, heat and motion, including sense organs (eyes, ears, nose, etc.). The second is our sensations or feelings (about things). The third – our perceptions, and the fourth – our mental formations or the mulling over in our mind, the choosing and intent of the action we take. The fifth is our consciousness or awareness.

These five “parts” of a being are constantly changing; none are permanent. Compare a current photo of yourself with your baby picture and you easily see how your body has changed. Your feelings and perceptions have changed, too, just as has your choices and the resulting actions. These ever-changing aggregates cause one’s self to evolve. Actually, there is no permanent “self,” only this unbroken, chain of aggregates, this evolutionary continuity of existence.

When the body “dies,” it is the first aggregate of organic matter that is dead. The other four cannot experience death, because they are not material. They are the unseen and intangible essences, sometimes called energy or spirit. Some religions might refer to them as the soul, but in Buddhism the idea of a permanent, unchanging soul or spirit, is rejected.

What causes us to change? It is our intention, volition and action. Just as the seed we plant and nourish grows into its intended and resulting flower or fruit, so we grow into the result of the seeds “inside” us that receive our nourishment. We have many kinds of both positive and negative seeds in our “store consciousness.” Some are inherited from our ancestors. Choosing which seeds to nourish creates who we are to become. Because we control our decisions and actions, we also determine our destiny. By deciding what we do we are deciding who we are to be.

This process of choosing and doing is called karma. Karma is not something that someone has, because there is no someone. According to Buddhist teachings, what is mistaken for a “someone” is this ever-changing process. In short, karma is who and what each of us is. It is the answer to the question, “Who am I?” The answer: “I am karma.”

Nirvana (Nibbana)

The concept of nirvana (Sanskrit) or nibbana (Pali) might be translated thus: ‘extinction’, ‘blowing out’, ‘freedom from desire’, the absence of dukkha or to cease. But those words or phrases really don’t explain nirvana. In fact, it is a concept that is almost unexplainable.

“No Buddhist tradition draws a definite conclusion for the meaning of nibbana,” writes Sayadaw U Dhammapiya, Ph.D., in his book Nibbana in Theravada Perspective, the very best book on the subject that I have ever come across. Venerable Dhammapiya is a most honored and respected Burmese monk from Myanmar, presently abbot of Mettananda Vihara Dhamma Yeiktha, a temple and Vipassana (insight) meditation center in Fremont, California. He is also a good friend.

“No single expression in any language can fully cover the true meaning of nibbanic experience without practice,” he writes. “The mere interpretations sometimes mislead readers to absorb different meanings.” I agree with Ven. Dhammapiya, that it is only through meditation that nibbana can be truly understood.

Trying to explain nirvana is somewhat like trying to explain the taste of sugar to one who has never tasted it, or trying to explain a color to one who is and was born blind. It is difficult, if not impossible.

Clever answers may be given to the question, what is nirvana. Answers may be explained in glowing terms, but no words can really give us an answer.

Nirvana is beyond words, logic and reasoning. It is easier and safer to speak of what nirvana is not. It isn’t nothingness or annihilation of self, because the dharma teaches there is no self to be annihilated.

In our attempt to explain it we use words which have limited meanings. It isn’t heaven; it isn’t purgatory, it isn’t Pure Land, and it isn’t the end. Nirvana is the Absolute Reality, which is realized through the highest mental training and wisdom. It is beyond the reach of the spoken or written word.

The Buddha said:

“It occurred to me, monks, that this dhamma I have realized is deep, hard to see, hard to understand, peaceful and sublime, beyond mere reasoning, subtle and intelligible to the wise. . . Hard, too, is it to see this calming of all conditioned things, the giving up of all substance of becoming, the extinction of craving, dispassion, cessation, nibbana. And if I were to teach the dhamma and others were not to understand me that would be weariness, a vexation for me.”

This is a clear indication from the Buddha himself that the extinction of desire (nirvana) is difficult to see, difficult to understand.

Buddhists call nibbana the Supreme Happiness, that it is the total absence of dukkha, that it is truth and reality.

Ven. Dhammapiya concludes, “Finally it is my contention that although a partial understanding is possible with a philosophical approach, without having personal experience of the meditative practice, one will not truly understand what the word nibbana really means.”

One last comment: One doesn’t have to die to experience nirvana. Most of us already have had momentary glimpses of it. I am partial to this quotation from the famous Lebanese – American writer Kahlil Gibran:

“Yes, there is a Nirvana: it is in leading your sheep to a green pasture, and in putting your child to sleep, and in writing the last line of your poem.”

Samsara

Traditional Buddhism usually translates samsara as ‘round of rebirth’ and ‘perpetual wandering’ to describe the continual process of again and again being born, growing old, suffering and dying. Further, this process is described as the unbroken chain of the five-fold khandhas-combinations, which constantly changing from moment to moment follow continuously one upon the other through inconceivable periods of time’ (Khandhas is the Pali word for aggregates, the five parts of a sentient being: body, feelings, perceptions, mind formations or thought process, and consciousness.)

This teaching or concept helps one to understand karma, which is important in understanding the continuity within samsara. one’s existence at the present time is subject to past existence(s).

Karma, the law of cause and effect, also can help us to understand samsara, and understanding the compounded nature of all things assists in understanding our interdependency, interconnectedness and our oneness.

Science tells us that it all began with the “Big Bang”. With that in mind, can you trace your origination back to that event? Or even before the Big Bang? How can this conclusion parallel the “act of creation” described in the Bible and Darwin’s theory of evolution?

Is everything experiencing samsara? It is easy to witness the constant change that takes place in all things, the coming into existence, the aging or deteriorating, the dying or ceasing to remain unchanged. This is the Buddhist truth of “everything is always changing; nothing remains the same”.

In Huston Smith’s book, Forgotten Truth (1976, chapter 4, The Levels of Selfhood), the author retells a Sufi story taken from Tales of the Dervishes. The story is titled, The Tale of the Sands. It can be found on the Web, but Huston’s book is available in paperback at Amazon.com. I highly recommend the book and the “Tale” for insight into the meaning of samsara.

Sutras (Suttas)

As explained in the “The Three Baskets”, the sutras (Sanskrit) or suttas (Pali) are the written versions of the Buddha’s discourses and the conversations he had with the sangha. They were not written by the Buddha, but his teachings as verbalized in his “sermons” or “lectures” were written down by followers sometime after his death.

There are many sutras on various subjects and of various length. It is difficult to say which ones are the most popular, because it depends on the tradition or school of Buddhism being practiced or considered.

For instance, among the many sutras favored or considered of great importance in the Mahayana tradition are three; they are known as the Diamond Sutra, the Lotus Sutra, and the Heart Sutra. Sutras are available in books and audio tapes, as well as on a variety of websites on the Internet.

The Buddha

Siddhattha Gotama (Pali) or Siddhartha Gautama (Sanskrit), who was born a prince in North India about 2500 years ago, acquired enlightenment after searching for it in most of the religions of his time. With his enlightenment came the name the Buddha, because the word Buddha simply means the awakened or enlightened one. Therefore, anyone in search of enlightenment could be called a Buddhist.

The Buddha never wrote down any of his teachings. He didn’t write his dhamma (dharma) – his teachings, but he delivered it verbally to all who would listen. He taught that life for the unenlightened is unsatisfactory, because it is filled with suffering and chronic frustration. Although there may be happiness in life, he taught, it is impermanent. Unhappiness also is impermanent; in fact, nothing is permanent.

To be born is unsatisfactory, to live and toil is unsatisfactory, to die is unsatisfactory.

The cycle of life is one of unsatisfactoriness, caused by ignorance, which in turn causes one to crave for things one feels will alleviate the unsatisfactoriness. This is a mistake, for only by reaching a state of desiring nothing can one attain true happiness. To reach this state one must turn inward, master one’s own mind and find peace within.

There are many books available relating the life story of the Buddha. However, it is sometimes difficult to separate the true facts of his life from fictional interpretations or from legendary stories. The Buddha was not a god; he was a man – a man who searched for and found enlightenment; a man who was asleep, but who woke up.

While the life of the Buddha is interesting, it is his dharma (teachings) that is most important.

The Dharma (Dhamma)

To understand the meaning of dharma (Sanskrit) or dhamma (Pali), the following is the definition of explanation given in Nyanatiloka’s Buddhist Dictionary, a Manual of Buddhist Terms and Doctrines, published in Sri Lanka.

“Dhamma: The ‘bearer’, constitution (or nature of a thing), a norm, law, doctrine; justice, righteousness; quality; thing, object of mind ‘phenomenon’ . . . The dhamma, as the liberating law discovered and proclaimed by the Buddha, is summed up in the Four Noble Truths and it forms one of the Three Gems . . . Dhamma, as object of mind, conditioned or not, real or imaginary.”

Dharma or dhamma, therefore, has many translations. By combining the English meaning of these words: teachings, truths, facts and natural laws, then emphasizing the definition dependent on the nature of the subject being discussed, one can usually understand the meaning of dharma in each instance. For instance, the meaning of dharma in the Triple Gem’s “Buddha, Dharma and Sangha” includes all of these: teachings, truths, facts and natural laws.

In our interpretations of the Buddha’s dharma, we think of the word as a label for the teaching of the Four Noble Truths and all the understanding and wisdom those “truths” imply.

The “Buddhism Teacher” actually could be called the “Dharma Teacher”, for it is the structure of Buddhism that is used to present acceptable “truths” or facts found in other teachings, including some religions, philosophies and psychologies.

It is not consistent with Buddhism’s dharma to be attached to Buddhism. This dharma, which teaches equanimity, non-attachment, tolerance, patience, compassion, loving kindness and emptiness would also be teaching bigotry if it were to exclude other enlightened and wise teachings. The basic dharma of Buddhism is “oneness.” Oneness includes, rather than excludes.

The growing interest in Buddhism in the western cultures, is partly due to the way the dharma is structured in the Four Noble Truths . . . so simply and reasonably stated, so seemingly logical and easy to understand, and so appealing to the intellect of searchers for an understanding of life and one’s place in it.

The Five Aggregates

What constitutes a human, or any sentient being, according to Buddhism?

A human is a combination of five aggregates (khandhas), namely body or form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations or thought process, and consciousness, which is the fundamental factor of the previous three.

The first is the Aggregate of Matter. Matter contains and comprises the four great primaries, known as solidity, fluidity, heat or temperature and motion or vibration. These primaries are not simply earth, water, fire and wind; in Buddhism they are much more.

Solidity is the element of expansion. Because of this element objects occupy space. Seeing an object is seeing it extended in space and we label it. he element of expansion is in solids, as well as in liquids. When we see a body of water, we are actually seeing solidity. The hardness of rock and the softness of paste, the quality of heaviness and lightness in things are qualities of solidity; they are states of it.

Fluidity is the element of cohesion. This element holds the particles of matter together. The cohesive force in liquids is so strong that they coalesce even after their separation. Once a solid is broken up or separated the particles cannot coalesce again, unless they are converted to liquid. This is accomplished by increasing their temperature, such as is done when welding metals. The object we see is a limited expansion or shape, which is made possible through the cohesion.

The element of heat or temperature is transmitted to the other three primaries. It preserves the vitality of all beings and plants. When we say that an object is cold, we only mean that the heat of that particular object is less than our body heat. It is relative.

Motion is the element of displacement and is relative. To know whether a thing is moving or not we need a point which we regard as being fixed, so the motion can be measured. Since there isn’t a motionless object in the universe, stability is also an element of motion. Motion is dependent on heat. Atoms cannot vibrate when there is no heat.

These Primaries are always co-existing and give birth to other phenomena and qualities; among them the five senses and their purposes: the eyes, which see; the ears, which hear; the nose, which smells; the tongue, which tastes; and the body or skin, which feels.

The second is the Aggregate of Feeling or Sensation. Feelings can be either pleasant, unpleasant or neutral and they arise from contact. Such contact as seeing something, hearing something, etc., creates an idea or thought, and we get a feeling about that idea or thought. An arising feeling cannot be prevented.

Feelings differ from person to person. We don’t all feel the same way about the same thing. Our feelings are dependent on our experiences and the way we process information. Not every person processes information in the same way, nor do they come to the same conclusion. And our feeling can and do change during our existence.

The third is the Aggregate of Perception. This aggregate perceives or recognizes both physical and mental objects through its contact with the senses. When we become aware or conscious of an object or idea, our perception recognizes its distinctions from other objects or ideas. This distinction makes us familiar with the object or idea when we sense it in the future. Perception is what enables memory. They can also be deceptive, and they too change during our existence.

A familiar Buddhist illustration tells of a farmer, who after sowing a field, sets up a scarecrow for protection from the birds, who usually mistake it for a man and will not land. That is an example of the illusionary possibilities of perception; this aggregate can produce false impressions. A perception can become so indelible on our mind that it becomes difficult to erase.

The fourth is the Aggregate of Mental Formations or Thought Process. This aggregate includes all mental factors except feeling and perception, which are two of the possible fifty-two mental factors noted in Buddhism. These factors are volitional; no action produces change or karma, unless there is intention, volition (choice), and action. Contact through the senses brings about the necessity of choosing an action and the action we choose depends upon our thought process, which is the result of our experiences and our individual evolution, including that of gaining or loosing wisdom.

The fifth is the Aggregate of Consciousness, the most important of the aggregates, because it is where the mental factors wind up. Without consciousness there can be no mental factors; they are interrelated, interdependent and coexistent.

The mind and its faculty is not something physical. It is concerned with thoughts and ideas. Forms are seen only via the eye, not via the ear, whose faculty of hearing is not that of the eye, etc. Thoughts and ideas belong to the faculty of the mind. The senses cannot think, nor can they mull over ideas, choose possible actions and arrive at conclusions.

Consciousness is made possible through the interaction of the senses. Thoughts and ideas originate in the mind, which in Buddhism is called the sixth sense. The five aggregates are not permanent; they are ever subject to change, and they do change as we experience life.

A human is composed of mind and matter, and according to Buddhism, apart from mind and matter, there is no such thing as an immortal soul, an unchanging “thing” separate from these five aggregates.

Thus, the combination of the five aggregates is called a being which may assume as many names as its types, shapes, and forms. According to Buddhism’s dharma, a human is a moral being with both positive and negative potentials. We make choices concerning which of these potentials we choose to nourish thereby becoming a part of exactly who each one of us is, in terms of characteristics, personality traits, and disposition. It is the potential of each human to gain wisdom and enlightenment. Buddhism teaches that each one of us is the architect of our own fate, and we will reap what we sow.

The Five Precepts

To better enable one to practice the three parts of the Noble Eightfold Path called sila or the morality group, i.e. realistic, skillful or right speech, action and livelihood, a person seeing the practicality of using Buddhism’s dharma in one’s life, and desirous of putting it to use, can take a vow (to oneself). This vow is known as the Five Precepts. In taking the vow, one is not joining any order or religion; he/she is merely stating an intention on how he/she intends on living life in a way that happiness is encouraged, where dukkha is eliminated or at least minimized, and where metta and karuna are practiced. These five precepts (in the form of a vow) are:

- I vow to train to abstain from killing anything that breathes, and I vow to encourage life.

- I vow to train to abstain from taking what is not given and I vow to encourage giving and sharing.

- I vow to train to abstain from sexual misconduct and I vow to encourage proper and respectful conduct.

- I vow to train to abstain from speaking falsehood and I vow to encourage truthfulness.

- I vow to train to abstain from liquor and drugs that cause intoxication and heedlessness and I vow to encourage the use of healthful food and liquids.

In taking into consideration these five precepts, I have created the following vow for participants in wedding ceremonies. The vow encompasses all five of the precepts.

The Buddhist Marriage Vow

“We vow to protect and encourage each other and all life, to be generous to each other and take less than we give, to speak truthfully and helpfully to each other, to nourish and to keep our bodies and minds healthy, and to treat each other with loving kindness and compassion.”

The Four Immeasurables

Metta, Kindness: May all beings always be content and satisfied with life, and may they possess within them the ability to cause themselves and others to be content and satisfied with life. His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Dr. Howard Cutler called this the attaining of “The Art of Happiness.”

Karuna, Compassion: May all beings always be free from dukkha (unsatisfactoriness, suffering) and its causes – among them desire, attachment, greed, anger, hate and ignorance, and may they always be able to act upon their feelings of sympathy, empathy and compassion.

Somanassa, Joy: May all beings always experience glad-mindedness, bliss and happiness, and may they enjoy sympathetic joy, the joy one receives from witnessing the happiness of others.

Upekkha, Equanimity: May all beings always be free from the poisons of judgment, attachment and anger, and may they always understand that things are as they are, but not indifferent and unwilling to make them better.

The Four Noble Truths

The Four Noble Truths make up the cornerstone of the dharma, the teachings of the Buddha. Here they are:

- To the unenlightened, life is filled with dukha.

- Dukkha is caused by selfish desire, anger and ignorance.

- Dukkha can be diminished, extinguished and eliminated.

- The way or practice leading to the end of dukkha is called the eightfold Path.

Dukkha is a Pali word (duhkha in Sanskrit) meaning “unsatisfactoriness.” Sometimes it is translated as “suffering,” or chronic frustration, anxiety and stress. It is not necessarily suffering, as we know it. Happiness, for instance, can be unsatisfactory due to its impermanence.

Here is another way to interpret the Four Noble Truths:

- Life can stink

- Because of our ignorance,

- But there’s a way to make it smell good.

- Here’s how.

The Noble Eightfold Path

The path leading to the end of dukkha, or the Way to make life satisfactory, is called the Eightfold Path. The Path is known also as the “Middle Way,” because it avoids two extremes, one extreme being the search for happiness through the pleasures of the senses, and the other being the search for happiness through self-mortification (shame, humiliation, regret, etc.) in different forms of asceticism (severe, hermit-like, secluded, etc.), which is painful and non-productive. It is divided into three stages: morality, equanimity of mind, and wisdom and insight.

Although the word “right” is often used in expressing the Path’s wisdom, ethical conduct and mental discipline, it is helpful to also think in terms of the words “realistic and skillful.”

Here is the Eightfold Path:

Wisdom (Insight)

- Right, realistic and skillful understanding.

- Right, realistic and skillful thought.

Ethical Conduct (Morality)

- Right, realistic and skillful speech.

- Right, realistic and skillful action

- Right, realistic and skillful aspiration (livelihood)

Mental Discipline (Equanimity of mind)

- Right, realistic and skillful effort (exertion)

- Right, realistic and skillful mindfulness (attentiveness)

- Right, realistic and skillful concentration

Following the Eightfold Path is an evolutionary process through many states of spiritual development until the ultimate goal is reached, which is enlightenment.

Practically the entire teaching of the Buddha is concerned in some way or other with this Path. The Buddha explained it in different ways and in different words to different people, according to the stage of their development and their capacity to understand it.

All eight elements are linked, and each helps to cultivate the others. They are not listed in order of importance, nor are they to be followed one at a time. They should be followed to the best of one’s ability all at the same time. When practiced, when you try to live your life by using these guides, you are perfecting the three essentials of Buddhist training, namely: Ethical Conduct (Sila), Mental Discipline (Samadhi) and Wisdom (Panna).

The Paramitas (Perfections)

The Paramitas hold an important place in Buddhism, especially in the Mahayana tradition, because it is an expression of what one should strive for if one wants to live life in a skillful, realistic, enlightened and wise way. In substance, the Paramitas point the way for living life by practicing metta (lovingkindness) and karuna (compassion).

The Paramitas are sometimes listed as six and sometimes as ten. As six they are:

- Generosity (Liberality)

- Conduct (Morality)

- Patience (Forbearance)

- Energy (Diligence, Industrious, Hard Work)

- Meditation

- Wisdom

As ten they are:

- Generosity (Liberality)

- Morality (Conduct)

- Renunciation

- Wisdom

- Diligence (Industrious)

- Patience (Forbearance)

- Truthfulness

- Resolution (Determination, Purpose)

- Lovingkindness

- Equanimity

Practitioners of the Paramitas are concerned about the welfare of all beings. Therefore they:

- strive to help others to be happy and secure by giving, without first investigating whether or not they are worthy,

- avoid doing them any harm by observing morality,

- strive toward performing tasks without hope of obtaining wealth, fame or privileges, and avoid the seeking of pleasures so that morality can be perfected,

- strive for insight, for wise and clearer understanding of what is beneficial and injurious to themselves and others,

- constantly exert energy and enthusiastic effort for the happiness of themselves and others,

- practice patience through compassion and lovingkindness by realizing the imperfections of ourselves and others,

- strive to be reliable, honest, truthful and dependable by not breaking promises, pledges or oaths,

- are determined to work constantly for the welfare of ourselves and all beings,

- reflect lovingkindness and compassion through the practice of kind and helpful acts toward all beings,

- harbor no thoughts of expectation or reward for our actions through the practice of equanimity.

The Poisons of Life and Their Antidotes

The cause of human suffering, as explained in Buddhist terms, is greed, anger and ignorance. These negative traits and fundamental evils are called the “Three Poisons,” because they are dangerous toxins in our lives.

Not only are they the source of our unquenchable thirst for possessions, and the root cause of all of our harmful delusions, but they are also painful pollutants, which bring sickness, both physical and mental.

Greed’s companions are desire and lust, and these passions and attachments cause us to want to get hold of things and to have more and more of them.

Anger’s friends are hatred, animosity and aversion, which cause us to reject what displeases us or infringes upon our ego. Ignorance, which is “not knowing,” especially not knowing our true nature, paves the way for delusion or in our believing something that is false.

These poisons fill our lives with suffering, frustration, unhappiness and unsatisfactoriness. They cause us to make unskillful decisions, which can affect our future and cause us to be self-serving and dishonest or unethical and immoral.

They are the roots of not only our own pain and misery but those of our loved ones and of society’s.

Fortunately, there is a way to eradicate this trio of contaminants. The practice of loving kindness and compassion is the medicine and enlightenment is the antidote.

Many of us are apt to be dominated by one of the poisons. Even when one dominates the other two are always lying dormant, like dry seeds that can sprout whenever nourished.

If one is dominated by anger, one tends to have unrealistic expectations, to be depressed or obsessed over political views, real or imagined enemies, or any of life’s negative delusions.

If the dominating poison is greed, then it can be manifested by stinginess, hardheartedness, hoarding or self-indulgence. One tends to be attached to one’s own ideas or to material things, thinking that more is better and that getting things will bring happiness.

When we are ignorant, we are not realizing our potential for experiencing happiness, which is our true nature, our buddhanature. Ignorance causes insecurity and a feeling of weakness, powerlessness and apathy.

Buddhist teachings tell us that because of our connectedness, these personal poisons are reflected in our society.

Greed, for example, is reflected in the destruction of the environment. Such reflections, however, are impermanent, changeable and transitory. They can be transformed for good.

Anger, for instance, can cause us to rally against intolerance, injustice and immorality.

While greed reflects insecurity and anger reveals vanity, ignorance articulates naïveté concerning knowledge and understanding of life’s realities.

One reality is that we don’t all think alike.

Because of culture, religion, nationality and numerous other separators, including our individual experiences, one’s thought process isn’t always the same as another’s process and conclusion.

These factors hide from us our connectedness, interdependence and oneness.

Flocks of birds and schools of fish often reflect this oneness with synchronized flights and swims and instantaneous turns. Their oneness is apparent, as it also is when exhibited by tribes, indigenous groups and inhabitants in the more isolated parts on our planet.

But for most of us this display of oneness is lacking.

Aware of their many similarities, multiple races and ethnicities attempt to live together harmoniously but seem sometimes severely handicapped by their impeding differences. Still, our oneness is factual.

If we are aware of the “Three Poisons,” their causes and their cures, we can bring about a wonderful metamorphosis.

Through the practice of loving kindness and compassion, these bitter poisons can be changed into sweet nectars, from which will evolve true happiness, replacing the fakes and counterfeits we have become used to.

When we realize our interdependence, our connectedness and oneness, we rid ourselves of the poisons that keep making us sick.

The Triple Gem (The Threefold Refuge)

The Triple Gem or Gems, in Buddhism, are sometimes called the Three Jewels. They are referred to when one takes the Threefold Refuge, which every serious follower of the teachings of the Buddha (dharma, dhamma) can take. When taking such refuge, the individual puts his whole trust in the Buddha, the dhamma and the sangha.

The Buddha, or the Enlightened One, is the teacher who discovered, realized and proclaimed to the world the law of deliverance, which is the rescue from one’s own enslavement, danger and ignorance. The dhamma is the law or truthful and practical deliverance, and the sangha is the community of the disciples or followers, who have realized or are striving to realize the law of deliverance.

A deeper meaning or interpretation of these Three Gems is that when one takes refuge in them, he/she is calling upon one’s own buddhanature, the potential buddha within each one of us, to dominate when deciding our intentions, choices and actions. He / She also is taking refuge in truth and enlightenment and in those who are or who seek to be enlightened.

The Threefold Refuge or pledge, when given or taken in the ancient language of Pali, still used in the Theravada tradition, is a beautiful sounding chant than can be heard in temples throughout the world. It is easy to memorize, because there are really only five words to remember. Then you can chant it along with the temple monks.

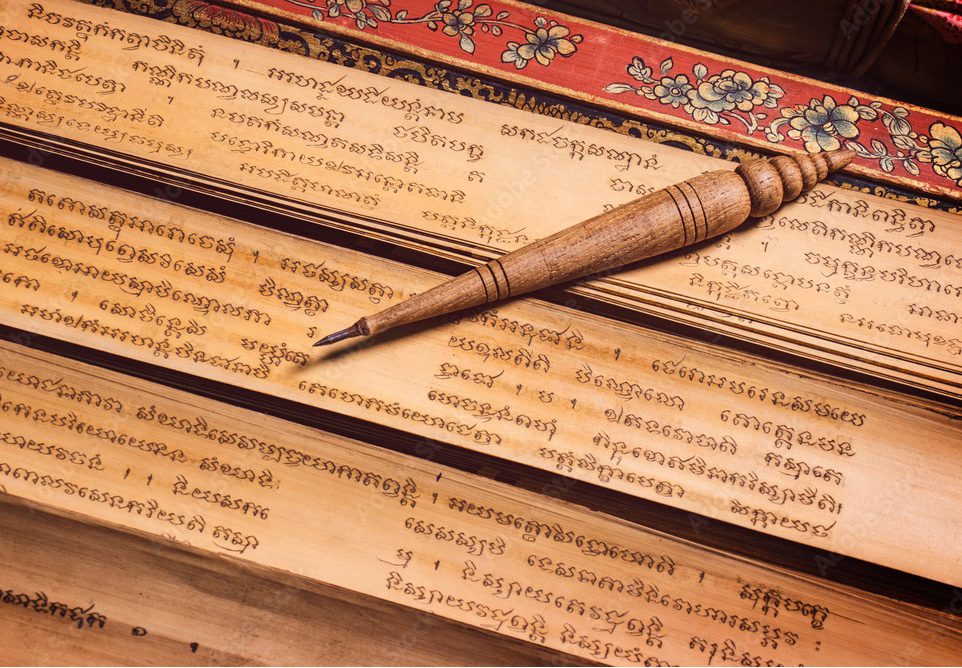

Three Baskets

The Three Baskets are called the Tipitaka in the ancient language of Pali and the Tripitaka in Sanskrit. They identify the basic scripture or canon at the heart of Buddhism’s teachings.

What the Torah is to Judaism, the New Testament to Christianity, and the Koran to Islam, so are the Three Baskets to Buddhism. They form the foundation of the written word or dharma.

The teachings are divided into three parts. The Vinaya Pitaka is the collection of texts concerning the rules of conduct governing the daily affairs within the sangha (the community of monks and nuns during the Buddha’s time). The Sutta Pitaka is the collection of discourses attributed to the Buddha, and the Abhidhamma Pitaka is the collection of texts concerning the nature of mind and matter.

Before the teachings were written down, some five hundred years after the time of Siddhartha, the Buddha, the teachings were memorized and taught orally.

The earliest writings of the texts were on long, narrow leaves, sewn together on one side and bound in bunches, then stored in baskets, therefore the origin of the name, the Three Baskets.

Vinaya Pitaka – Discipline Basket

The first basket, the Vinaya Pitaka, explains and analyzes the R and Rs set forth for the monks and nuns to follow in their monastic life. The several hundred regulations are concerned with basic morality, but include details on robe-making, monk and nun interaction, and other essentials for successful life in the sangha.

Sutta Pitaka – Discourse Basket

The second basket, the Sutta Pitaka, is similar to a transcription of the conversations between the Buddha and the monks and nuns, the Buddha’s sermons and verbal discourses and teachings. Additional information about the Suttas (Pali) or Sutras (Sanskrit) are discussed under those titles.

Abhidhamma Pitaka – Philosophy Basket

The third basket, the Abhidhamma Pitaka, which means further or special teachings, is a systematic philosophical and sometimes “scientific” description of the nature of mind, matter and time.